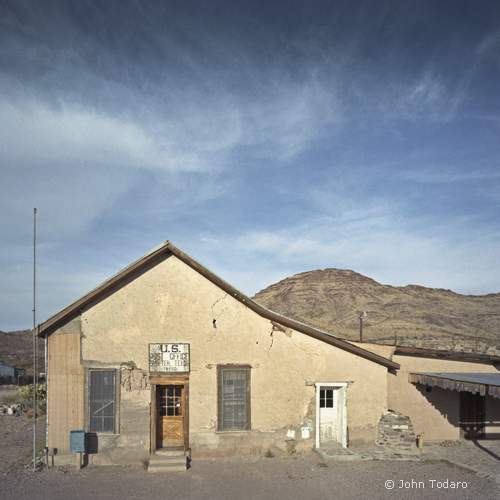

A New Mexico photograph published last summer, and moved back into the queue this morning. Click on it for a larger version.

Trips West

Black and White Dune Photography II

I’ve gotten absorbed with these dune photographs for the last week and ask for your patience, especially if this sort of image provides you with no ignition.

The pictures were taken at various times during the last twelve years and have been mothballed until now. They were recorded on archaic film with analogue equipment (none of which I’ve yet surrendered). I scanned the pictures using an obsolete Minolta Dimage Scan Elite (which I bought on eBay after my original was fried in a lightning strike). The good old stuff.

Once you’ve scanned your film and it’s been nestled into Photoshop, it has been rescued from obsolescence–a good thing, I suppose–although as a child of the previous century, I feel the pangs of resistance.

The picture is from the Little Sahara Recreation Area in north central Utah. I have some other images from this locale which I’ll be posting later.

(The camera: Contax G2; 28mm Zeiss Biogon)

Black and White Dune Photography I

Love Always (Postcards for Miles)

Some Words for Micro Four Thirds, Prime Lenses (and the New Mexico Plains)

I promise this won’t be a review. Well at least not exactly. I will take this opportunity to crank out a bit of a “rolling plug”

I started working in the 4/3 format earlier this year using a Panasonic Lumix GF2 and a pair of those morsel-sized a la carte lenses. I have the 14mm and the 20mm primes which translate into a 28mm and 40mm respectively (0n a 35mm camera). These lenses are sometimes referred to as “pancakes” and we can rest assured that whoever conjured up such a name had a functional imagination. (We could also call them truffles, or slightly flattened cupcakes).

There’s been plenty of hype about this format along with all the hyperactive comparisons that we’ve come to expect at regular intervals every time a new product arrives. Rejoice in knowing that I won’t contribute anything else to that particular subject.

Those in love with increasing numbers of megapixels got their fix a couple of years ago when the format first surfaced. Plus there was a larger sensor. We now know that the RAW files produced by any of the Olympus or Panasonic bodies will serve you well if you caress them properly. But … be warned: If you own one of these cameras, don’t doubt for a minute that you’ll be seriously tempted by the next wave (spelled: NEX 7). If you decide to chase that carrot next February it will be your strictly your decision. My advice is to sit back and relax. Be a tortoise. Avoid the bleeding edge. They’ve stumbled onto a nice balance between performance and weight here at the moment — and we might as well enjoy it.

My friend (and fellow photographer) John Ellsworth told me last week that handling one of these micro 4/3 lenses is something like handling a “chess piece”. I enjoyed the thought. (He was actually referring to the Olympus M Zuiko 45mm f1.8, another lens which I finally sprung for). John and I are old enough to remember what 120 film cameras feel like when they’re hanging around your neck.

Anyway, the photograph above was taken with the Panasonic GF 2 (and the 20mm f1.7). With this camera, I’m able to focus the picture and adjust the exposure by the very simple act of touching the screen, (something which I still regard with amazement). I’ve been surprised to read that touch-screen navigation has aggravated some photographers. It seems there’s those who’d rather twist a dial. I’m fine with the touch screen because it appeals to my severely limited capacity to follow instructions. Look at it this way: touching a screen requires only one finger and turning a dial takes two.

I’ll admit that since I bought this camera I’ve been cornering opportunities to explore the speed of these lenses. Believe it or not you can perform a variation on street photography far from any lamppost. The 20mm lens is also capable of producing shallow depth of field. In Japan they call this effect “bokeh”. I’m still uneasy with the pronunciation but I’ve been using the word a lot lately because it’s a lot sexier than saying “shallow depth of field”.

At any rate, my camera was hand-held for this picture and was therefore free to shoot six or seven variations in several positions and all in less than a minute. I feel like I’m playing jazz when I’m not off mucking around with my tripod and its multitude of extended joints. Let’s face it; tripods are a bit clunky by nature. They also require at least three fingers to operate. That makes them even more complicated than turning a dial and much more so than touching a screen. I use them strictly when I need to.

Enough with cameras. Let’s move on to the West.

I’ve visited the eastern plains of New Mexico many times over the years and I always wonder why everyone else is driving though the place as fast as they can. I concede that there’s nothing much to see except for open space, which for me, is pretty much the point. This is not the Grand Canyon. If you spend any time out on the plains your expectations for normal landscapes will need to evolve. The scenery basically comes down to various combinations of grass and clouds, and (for better or worse) the ever present evidence of humans which usually takes the shape of a fence. There’s cows everywhere but one thing about the plains is that you hardly ever see the people. That’s okay, because their absence creates interest.

One visit didn’t involve taking any pictures. Many years ago my wife and I took a train ride west from Long Island. We took it all the way to Albuquerque just to see what it was like.

It was long. Even compared to a bad day at the airport, this was a trip which slowed time down to a slurpy crawl. It seemed like years before we were rid of the east (but once we were past Chicago things did get more interesting). My favorite part was the morning after the second night. We got up and walked groggily through the train to a very lovely dining car. I remember cloth napkins. We were seated at small table and had the most delicious breakfast with a very compelling view. We were now chugging through the plains and were finally situated in New Mexico. All you could see was mile after mile of grass, clouds and the ubiquitous fences of ranching. It looked something like my picture up above except it was brighter because the sun coming up.

As I said, it wasn’t a day that I used my camera. The train window took all the pictures and we stored them in our memory.

Lover’s Quarrel

Wall Images – Santa Fe Area, August 2011

Fort Union – Images II and III (Canon G10)

The pair of verticals were taken at Fort Union, in New Mexico (discussed in my previous post). On the trip, I used my older Canon G 10 for situations like these because they seemed to be asking for a telephoto. The tendency of telephotos to simplify potentially distracting elements can be very helpful in some situations. The Canon G series cameras (as well as the S series cameras) have well-deserved reputations for zoom lenses with lots of depth of field, even when maxed-out.

Fort Union is a good place for anyone who enjoys watching clouds, especially through a window. Being in New Mexico, just east of the Rockies, there’s no shortage of spirited skies. The adobe walls also provide opportunities to frame “blue within red”. The ruins create scale, and more importantly they create moods. Imagine photographs of the same clouds in these pictures without the foreground walls. Those pictures could be good ones too, but would be entirely different animals.

It would be an enjoyable project to photograph the sky through an individual window at this fort every day for one year.

Fort Union – Image 1 (Panasonic Lumix GF 2)

Fort Union is an historic site administered by the National Park Service which preserves the remains of the largest Federal fort along the Santa Fe Trail. It’s located in New Mexico. The fort’s moment in history commenced during the latter half of the 19th century and lasted up until the arrival of the railroad. It’s an imposing reminder of what a city-sized outpost on the Santa Fe Trail might have once been like. After 100 years, it’s still surrounded by many square miles of prairie and a view of the Rocky Mountains. Although the wagons have long since vanished, it’s become a striking place to photograph, and one with abundant amounts of quiet.

This is the first of several pictures from the fort, a horizontal image with a view through a standing wall. The sun was caught at a good angle here, especially for revealing texture.

If you look closely, there’s a curious smaller window at the bottom of the rear wall. The view through that window has been “shortened” by a rising knoll of grass behind the fort. The picture was captured with my Panasonic GF 2 and its normal 20mm lens.

Melancholy and the Mother Road – San Jon, NM

This picture dates from just a few weeks ago when were exploring an especially ragged section of Route 66 somewhere in the vicinity of San Jon. The town lies in the eastern part of New Mexico very near the Texas border, a sparsely populated region with an occasional mesa and abundant mesquite. The old route veers south of the interstate here, and leaves the pavement behind.

The evening was coming on and it wasn’t clear if we’d gotten lost. My son was up front, and my wife was in the back squinting at the Delorme Atlas wondering if we were near San Jon or another town called Lesbia. Not much appeared to be left of either place and there wasn’t anyone around to ask.

It grew darker. On the north side of the road we slowed down and crept up to the scene in this photograph. I turned off the ignition because the sky was exquisite. Needless to say it was time to get out the camera.

Behind the former gas station were some brushy remains of buildings that might have once been a motor court. The place had clearly seen better times, and with the final touch of a collapsing roof was nothing short of haunting.

Tucumcari – Five Photographs At Dawn

At pre-dawn on the morning of September 3rd, I left the family asleep at our motel and drove over to the historic downtown section of Tucumcari. It was deserted. The warming glow of the eastern sun had stretched its fingers across the plains and was just reaching the first group of buildings. I took some pictures using a normal lens. I’ve admired similar pictures taken by photographers like Joel Meyerowitz and Stephen Shore, although their work was done with large format cameras.

For these photographs, I was using my new Panasonic GF2 which permitted me to handhold the camera. This is easy enough to do because the 20mm lens is a fast one. To me, avoiding a tripod in a situation like this can produce a pleasant combination of spontaneity and connecting ideas. The project was wrapped up in about a half hour. This group of five represents my favorites. You can click on any of the thumbnails to produce larger pictures.

Tucumcari. Tucumcari.

When entering New Mexico from the east on I 40, the first town to seize your attention is Tucumcari. It’s located on what is now called “Historical Route 66” and is said to boast the largest collection of original motel signs from the glory days of the famous highway. The town, despite its multitude of splitting seams, is still a wonderful place to gas up, eat, and locate a cheap motel.

On our August trip we drove into Tucumcari three separate times (not an easy thing to do considering it’s really in the middle of nowhere).

The town is divided into two parts – the historic downtown (which looks desperately in need of a friend), and the strip of Route 66 with its ragtag collection of cafes and motels. Honestly, it’s difficult to say what’s original out on the strip. Everything blends into a nicely textured, slightly-disintigrating mosaic. There are old Chevys anchored down in front of even older motels and none of it has the look of corporate tourism. We stayed at one, in an effort to avoid patronizing the “big name” chains in town.

Selecting our motel took a bit of effort. First we surveyed the lineup because there are least a dozen separate Mom and Pop operations. Each have historic signs (complete with missing bulbs) and buildings in similar states of disrepair. The motel owners are in hot competition with each other (with many advertising rooms for under $25). Such astonishingly low prices gave us a bit of hesitation, but we were determined to snub the big chains. The place we settled on was run by a charming couple from Hyderabad (fellow vegetarians) who gave us some useful tips for cooking Idli. We thoroughly enjoyed our conversation with the owners along with our stay in their old motel.

There’s something about this town that made me feel like the country’s going to be okay.

Tucumacari has a fascinating modern history. It goes something like this:

1700’s – Apaches and Comanches take turns with the region bringing in their thriving nomadic economies. This included raiding, hunting and collecting local herbs – a system far superior to the current model.

1901 – A tent-city springs up during railroad construction. The village (now in its infancy) is known as Ragtown and later as Six Shooter Siding

1908 – Trains are everywhere. Tucumcari is finally named “Tucumcari” (a Comanche term for the nearby flat-topped mesa).

1926 – Route 66 is famously paved into town replacing wagon yards and blacksmith shops with motels and gas stations. You can still see chunks of original pavement both east and west of town.

1960’s – Interstate 40 is built, an event which effectively served Route 66 with marching papers. The country begins to look the same everywhere.

Today there is renewed interest in the Route 66 phase of the town’s history. This is a healthy sign of revolt. The photograph above is a good example of local architecture. The building was done in a style unique to Tucumcari – one which effortlessly combines original with retro (easy enough to do since everything looks like its falling apart). No one seems concerned with what determines originality here and it doesn’t much matter because the town is full of character.

By the way, “La Cita” in Spanish means “The Date”… a curious name for a building that appears to house both a florist and a Mexican restaurant. We didn’t get a chance to eat there (or order flowers). Maybe next time.

Thunderstorm Near Taos

After yesterday’s post, I found another unpublished image of a thunderstorm, again from a trip out west. This one was photographed near Taos, New Mexico. (Incidentally, both this image and yesterday’s were shot on transparency film using my Contax G2, a camera that once went with me everywhere.)

In light of the relentless drought which is blanketing parts of the Southwest and Plains this summer, these images are especially refreshing. “Impending Rain” are two words that would make a lot of folks happy right now. During a normal year, anyone who has spent an August in New Mexico will likely agree that the state has assembled all the right ingredients for spectacular skies. Rain is the reason for that. Afternoon thunderstorms routinely fill the sky with enough drama to make an English major happy.

Taos is bordered on the west by sagebrush plains and the northern flow of the Rio Grande. It is country that is home to a large number of black volcanic rocks, many the size of beach balls. It’s also an area with an abundance of thunder. It was in such a setting that this picture was taken. It was a fast moving front and the sunflowers did their job – a dozen delicate suns caught in the light of an approaching storm.

Thunderstorm Near A Remote Corral

It’s nearly August, a month which has found us wandering west for so many years that it’s difficult to recall one trip from another. Several summers ago we were emerging from an overnight camp in the San Rafael Swell – a rarely-visited desert area in south-central Utah. The region is roughly the size of Long Island and is criss-crossed by a handful of graded roads. It’s easy to to end up in a bit of a mess in this place, and so one needs to think long and hard before making any sort of turn. We were dusty, in need of showers and speculating on the location of the nearest gallon of iced tea. Mostly, we were hoping our little rental car would eventually make it to some sort of Mexican restaurant. The nearest town of any size was Price, some 35 miles to the north.

In the back seat my young son gazed out at a land which was only beginning to scratch his imagination. While making our way across the grasslands which rise onto a plateau to the west, huge storm clouds began to gather. This was an event which quickly rewrote the landscape. As the winds picked up, the heat began to back away like a Fundy tide. The west is a mercurial place. I pulled over near a corral and removed my tripod from the trunk. A picture was taken between the opening salvo of raindrops with the smell of ozone releasing the floodgates of memory. In the car, my wife was begging me to get back in.

Reading Summer Streams

During the last four summers we vacationed in southern Utah, a place more famous for massive canyon walls than trickling desert streams. But the two sometimes combine to make a hike in arid country far more refreshing than you might expect.

In Capitol Reef National Park we’ve followed stream beds for an entire day. In nearby Escalante, Pine Creek is another place to do this. The creeks in canyon country are generally shallow and often flow across naked rock for miles. In some spots they pass through slickrock gorges that are so narrow that the trail essentially becomes the stream. Before venturing into any of these places, one needs to check the weather because sudden downpours can produce flash floods.

Surprisingly, even in mid summer the water in the streams is frigid. We’ve taken hikes in August where you’re either wet and shivering or baking in temperatures that approach 100 degrees. It all depends on whether or not you’re in the water. Get yourself wet and your teeth chatter. Hike back into the sun and you open the oven door.

Hiking Sulphur Creek in Capitol Reef involves so many stream crossings that you can’t keep track of them. After a half a mile or so, any hope of dry boots is squashed. The easiest thing to do is simply get in the stream and stay there. There are sandals designed for this. There are also a number of waterfalls passing over rock chutes that require careful navigation. Because the canyon walls rise hundreds of feet in these places, you either find a way to climb through the pour-offs or turn around and go back. You have two choices for many of these hikes – either get wet or completely soaked.

Aside from enjoying the water, I always get out the camera. The images I’m looking for are in the cloistered places where the creek plunges into the shade of canyon walls. It’s here that I’ve found the most compelling reflections. When studying the way the water looks from a variety of angles, you sometimes find pockets of irresistible color. In the shade, reflections of rocks, leaves and sky become deeply saturated.

It’s been in these sequestered locations where I’ve found many of my favorite pictures. It’s no coincidence that they’re also some of my favorite places.

Hasselblad 903SWC … rambling thoughts

The image is a another from Shafter, TX done with my Hasselblad 903 SWC. The picture from my previous post today was taken about an hour earlier.

Interestingly, this picture was published in a January 1997 Shutterbug article for reasons that now seem strangely outdated. In those days, the magazine devoted one issue per year to the latest and greatest 120 film cameras, with additional articles about photographers working in that format. Due to the equipment discussions, there was excitement generated by that particular Shutterbug, and it was probably the closest the magazine ever came to having a “swimsuit” issue. Back in 1997, it was an honor to have one’s work show up on those pages.

Things changed quickly. These days it’s hard to imagine a time when none of us knew what a pixel was. To their credit, Shutterbug made the transition too. Nowadays the discussion revolves around the mystique of the digital SLR and the latest revolution in point and shoot.

In spite of all that, there are still those (including myself) who savor the look and feel of 120 film cameras such as the 903. Like most people these days, I own a digital camera, but I’m not giving up my Superwide anytime soon. I keep a few rolls of film on hand and have no issue with scanning it. An extra step to the digital work-flow is barely a hassle and more than worth the effort.

Some technical thoughts about using the 903 Superwide:

The detachable viewfinder made for this camera is the easiest way to view an image. Over the years when taking a picture, I’ve generally left the viewfinder on and used it to compose my photograph. If you’ve never owned the camera, keep in mind that when using the detachable viewfinder, the lower portion of your view is obscured by the lens barrel. I’ve always gotten around this little snag by turning the camera sideways in order to view the lower part of my image. For focusing, I use the hyperfocal-focusing marks on the lens barrel.

If greater precision is needed for composing and focusing, a ground glass back is available from Hasselblad and may be used in conjunction with any of the prism finders. I use it with the PM 5. Using the ground glass back with a prism finder requires that you remove the film back, and that you’re okay with viewing an upside down image. It also requires a shutter locked in the open position with a good cable release. Once you’ve done all that and your picture is composed and focused, the ground glass back (and prism finder) is removed and the film back is reinstalled. Obviously, all this is done with the camera on a tripod.

Additional photographs I’ve taken with the 903 may be seen by clicking on this link:

https://johntodaro.wordpress.com/category/viewpoints/square-format-hasselblad/

Keep in mind that colors and contrast of the images at this site will be most accurate when viewed on a calibrated MAC monitor. This is most relevant to photographs that have a wide range of contrast such as many of the ones I photographed with the 903.

If you’ve got any other questions about the camera, feel free to post a comment.

Romancing the Hasselblad – Shafter, Texas

Shafter, Texas sits in an area so sparsely populated that it makes much of the rest of the west seem tame by comparison. It is a region of vast ranches, grasslands and desert scrub which occupies hundreds of square miles south to the Mexican border. In the distance are isolated mountain ranges that receive little rainfall and almost no visitors. To the east is the nearly one million acres of Big Bend National Park. The last time I was in Shafter, there were less than ten citizens.

This is an area which gives new meaning to the word remote.

I’ve returned from various trips to this part of Texas with some of my favorite landscapes. In almost every instance, I used the Hasselblad 903 SWC because it’s a place where the exceptionally wide Zeiss Biogon can do it’s thing.

Things to do in Moab … did he say, “admire the flowers?”

Consider this post a recess.

I recently was shopping in the health food store in Sag Harbor on Eastern Long Island and I was wearing my Moab hat. Someone came over and asked:

“What’s a Moab?”

A question like that isn’t that uncommon out here in the salt-soaked forests east of the Hudson River. In fact many people around are likely to assume the name Edward Abbey is an Edward Albee typo.

Me and Moab go back a long ways. It began in August 1978 when I was passing through what was then a town with only two places to eat. We were in one of them ordering breakfast and preparing to head up to nearby Arches National Park. I was traveling with a close friend and my brother. It was the “salad years” for three of us and thanks to Edward Abbey, we had recently discovered Utah.

At the restaurant, I phoned home and my father informed me that Sagamore Hill National Historic Site had called. My father hated talking on the phone so I considered myself lucky. The three of us fished around for pocket change and I rang them up. The curator needed a staff photographer after Labor Day and I was offered the job.

I took it.

Many years later I returned to Moab with my wife and son and geez… had that place changed. They’d discovered over a thousand more arches inside the park. That made me feel old. Next they invented mountain bikes and all the people showed up. This was a clearly a town that had shifted gears since I first arrived.

You had to hand it to old Ed Abbey. He wrote Desert Solitaire and became the unwitting founding father of both Earth First and the Moab Chamber Of Commerce. Considering some of the pricey developments springing up, you have to wonder what he’d make of it all.

I don’t know about him but I think that it’s good.

Some in southern Utah won’t agree, but the vacationing eco-tourists and Europeans on holiday are living proof that their state doesn’t require any more roads or mines, or forests full of cows. The good citizens need to remember that green types tend to travel with plenty of the green stuff. If Moab is any indication, more wilderness might actually boost their economy.

Enough with that. Now onto the photographs.

Nowadays there’s lots of good photographers exhibiting in Moab. In fact, the last time I was there, I’d say there were more photographers than gas stations. All of these guys are very good, although in Moab and everywhere else in Utah they tend to be white guys over fifty – something like myself.

And so… where are my arch pictures?

Unfortunately, I’ve got a tendency to withhold pictures that people want to see the most. I can’t help it, it’s my nature. I have photographs of arches but you have to wait. At any rate, Moab is one sweet town to walk around. Remember, that’s coming from a guy whose hometown got some sort of award from National Geographic (I keep forgetting to read the little sign they put up across from our library).

Thus, from Moab, I have flowers. Yarrow, Lantana, Roses and a Sunflower, all of which were photographed around Main Street, some near my favorite restaurants. I don’t know if Moab is overrated for anything but it’s underrated for flowers. My advice to visitors: admire the flowers.

Some comments:

Yes, the Yarrow is dried up which in my opinion is the way it looks best – the place is a desert after all. The sunflower is complimented by a common garden hose which is the first one I’ve ever photographed. The final image is a fascinating one. I was struck by the way the two tripod legs looked and kept them in the picture. Photographers tend to avoid getting tripods in their photographs for obvious reasons but in this case, I let them be. It’s a self-portrait, of sorts.

There are good textures in these pictures. People have seen them at different shows and think I took them in Paris.

I didn’t. They’re just from Moab.

Now for some off topic family favorites… and the rest of the photographs:

Favorite Waffle: Jailhouse Cafe ••• Favorite Mexican Food: Miguel’s Baja Grill ••• Best Deal: 99 cent Clif Bars at GearHeads ••• Favorite Thrift Store: Wabisabi (where my hat came from) ••• Favorite Bookstore: Back of Beyond (where my t-shirt came from) ••• Favorite Muffin: Chocolate Peanut Butter Vegan Muffin at Love Muffin Cafe ••• Favorite Shower: Slickrock Campground ••• Favorite Snack: Apricot Suncakes, Moonflower Market, Inc.

Favorite Utah National Park: Capitol Reef (sorry Arches)

Favorite Book About the Area: Park Slayer Pursuit, a short book which my son wrote in 7th grade (sorry Mr. Abbey)

Bandon, Oregon – Hasselblad 903 SWC

This photograph was taken fifteen years ago, looking west from the left-coast at an ocean I’ve rarely photographed. It was November and I was high on a bluff in Bandon Oregon – an unpretentious town at the end of a dusty road with a surprisingly epic view of the Pacific. Something about this place reminded me of off-season Montauk and similar towns – timeless places putting on their winter clothes – communities that can be counted on not to change for the worse.

Admittedly the view of the ocean here was more like Montauk on steroids – scenery on a truly grand scale. Appropriately, I chose my Hasselblad 903 SWC – a medium format camera that came fixed with what quite possibly was the finest wide angle lens ever made – the 38mm f4.5 Biogon. This was a camera unburdened with bells and whistles and redundant gadgetry. With it’s detachable viewfinder and ability to accept a ground glass back, the 903 has reigned for years as the ultimate choice for wide angle devotees. Perhaps for this reason, the camera has earned it’s nickname “Superwide” although the number of people familiar with it on that basis is sadly dwindling. In the previous century when Hasselblads were in vogue both here and on the moon, the Superwide had a much deserved reputation for pinpoint accuracy and corner-to-corner sharpness. But now, due to the lack of a digital back, it sadly falls out of fashion with those of us producing millions of pixels. Perhaps its moon is waning.

My friend Jonathan who studies these things tells me that the 903 was first produced in Sweden in 1954 which also happens to be the same year I was manufactured. An early prototype was unceremoniously shipped to our shores around the time Charlie Parker was making his final recordings. With only minor modifications it has remained unchanged ever since. You can still buy it, or you can buy an older one and put a brand new back on it which will attach with no problem. That was the point. It was produced when things were still bench-made by guys who assembled things with a panache for precision. It was put together with sturdy parts and close attention to details. The damn thing worked. It felt good in your hands. When you put it back in it’s case and took it out the following spring, it didn’t need any improvements. Once you bought this camera there was no need to upgrade your operating system.

And so I am not yet ready for it’s elegy. Digital imaging is here for good and I’m not inclined toward orthodoxy whether it’s on one side of this argument or the other. I can live with the complexities of being a hybrid and will happily scan my film.

To see other photographs taken with the Hasselblad 903 SWC click on this link:

https://johntodaro.wordpress.com/category/viewpoints/square-format/

For a commentary about the use of the detachable rangefinder and ground glass back on the 903, go to this link:

https://johntodaro.wordpress.com/2011/03/26/hasselblad-903swc-rambling-thoughts/

Sequence Photographs Vol 2 – San Rafael Swell, Utah

Northeast of Capitol Reef National Park in southern Utah is a vast wild area– a complex of eroded sandstone landscapes known as the San Rafael Swell. For those impressed with numbers, the area occupied by the San Rafael (pronounced Rah-FELL) is approximately one million acres. By way of analogy, it’s about the same size as Long Island where I live– but unlike our Island, the Swell is not home to several million people. There are generally more canyons here than conversations, and you will sometimes encounter more rattlesnakes than visitors. Its seemingly endless array of stony washes, hoodoos, slickrock and isolated pools can be difficult to describe and sometimes hard to photograph with any justice. We’ve hiked and camped the Swell so often, I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve been there.

Anywhere else in the country the San Rafael would’ve been declared a National Park or Monument years ago. But in Utah (a state not lacking anything spectacular) the affairs of the Swell have fallen largely into the hands of the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management. There are several wilderness study areas under consideration, but the BLM (in case you haven’t heard) has had the occasional affair with mining, off-road vehicle interests and gas exploration. Currently, the Swell exists with both ongoing threats and a growing push to create a National Monument. For those motivated toward preservation, The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) is the principle group trying to save the place. http://www.suwa.org/site/PageServer

This past summer, we made several day trips in from Hanksville or Green River. In the silence and heat that can transform a summer’s stroll on slickrock into something that’s really gotten your attention, the camera can be a playful device to bring to that awareness.

On these hikes it was random passing stuff that stopped me. The look of a rock or a stick — the tread across sandstone. Textures and color — hidden corners of big places — the small things in a huge landscape.

In the canyons I collect details like I used to collect postage stamps when I was a kid. Back home I sort through the photographs and see how they look in groups. Once in awhile when sequencing pictures like this something comes together. I settle on an arrangement of three:

A Cottonwood leaf… polka dots raindrops on a rock… a dry image of lichens.